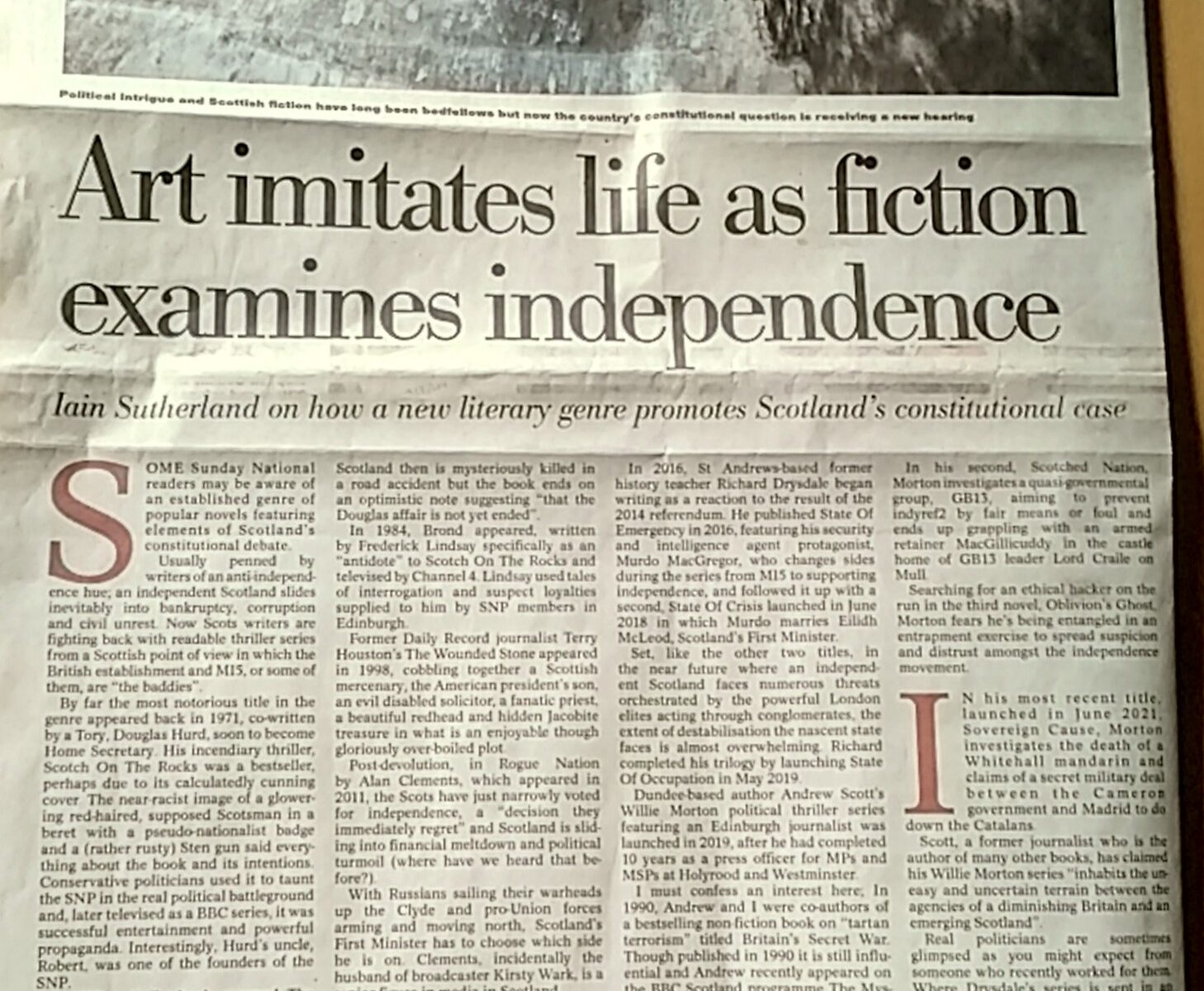

“Art imitates Life as Fiction Examines Independence” by Iain Sutherland (The National 4.2.22)

Seeking Agent…!

My career is a mish-mash of books published, reprinted, remaindered even, gone out of print, from a variety of publishers, mostly small Scottish publishers, few of whom had much promotional spend. Consequently, my career has lurched from book to book, publisher to publisher, to self-publishing to… nothing much. And yet, I’ve had a career, won prizes, well, A prize (that was 23 years ago now!) and eighteen books are out there, some in several editions, paperback, hardback, ebook, even one audiobook. When I started out, I was using a portable typewriter, though I’ve been an earlier adopter of tech, have had a website for around twenty years. Not that it’s done me much good. Anyway, I’m still at it, book after book, though now it’s getting harder to see where I’m going. Which of course starts to impact on my writing, negatively. If only… I had got an agent in those early days instead of sending to publishers and bashing away on my own! Because that would provide many good things, regular feedback for one, support, some order in my career. It’d be great and I remain hopeful. But, a funny thing, I’ve seen the beast that is the publishing world change, or mutate over these years. Now there are publishers that look different to Publishers and some that aren’t really publishers at all. In the same way, there are Agents and agents. I’m trying to contact these (agents and Agents) in the conventional way about my recent work but, hell, why not put an ad on here, I thought. Can’t do any harm. You never know who might see this. Probably nobody but…

Fictional Dundees

Bookweek Scotland Event

Looking forward to talking about my novels and Dundee history; representations of Dundee and environs throughout its history as depicted in fiction by me and other authors. I’ll be chatting to the reading group at Monifieth Library, Angus, on Tuesday 16th November from 2.15. The event is free but ticketed, as part of Scottish Book Trust’s #BookweekScotland programme. @BookWeekScot

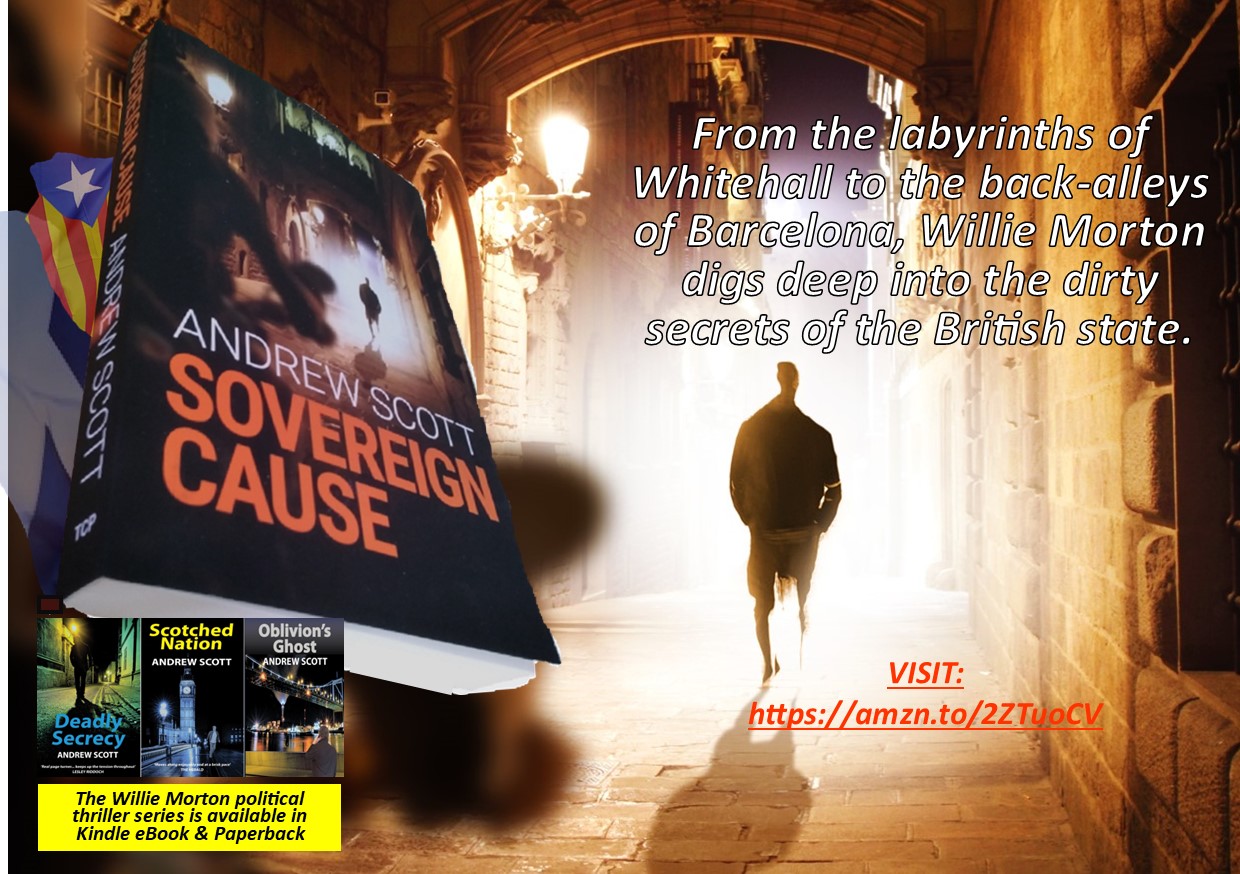

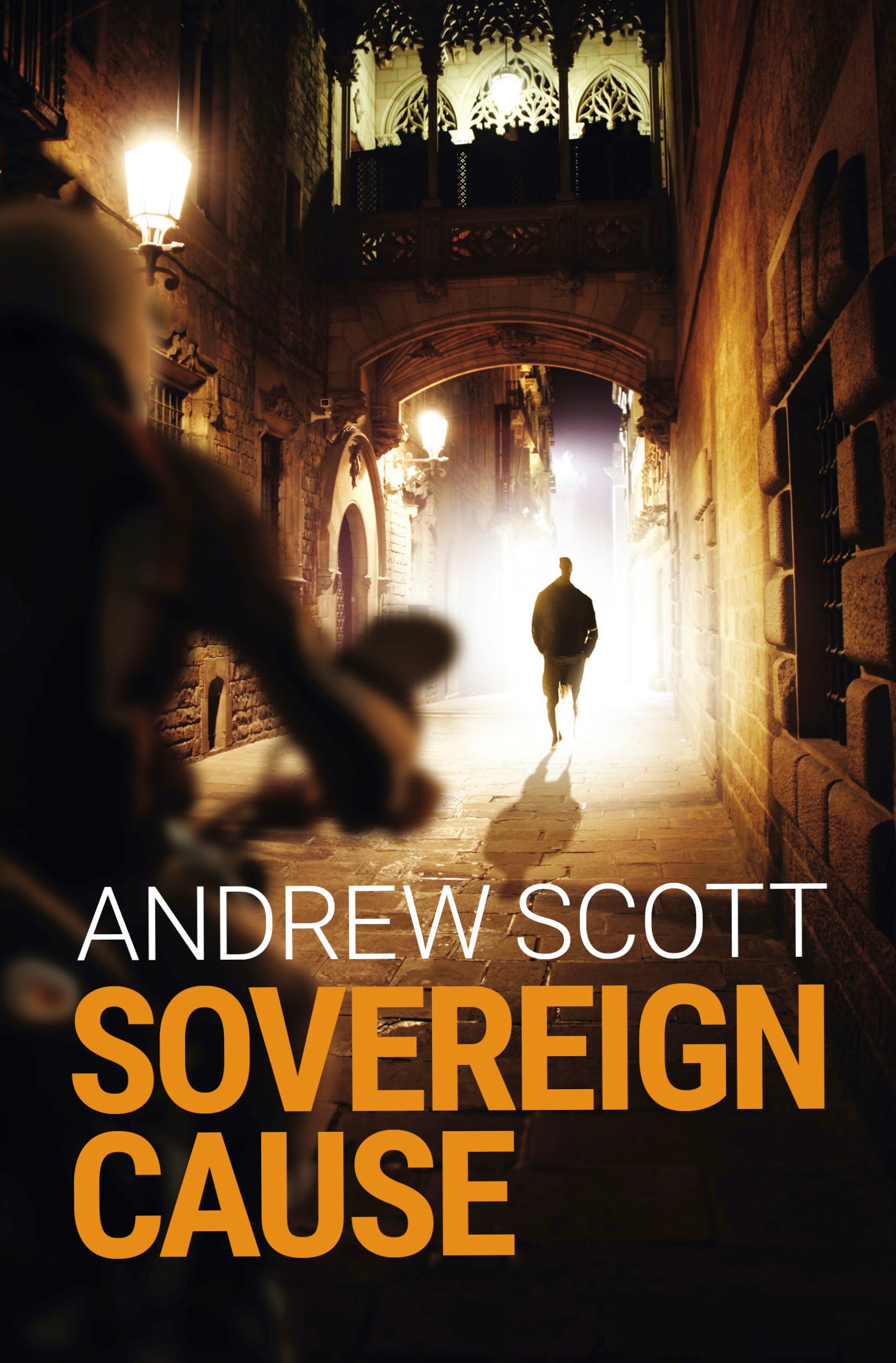

Pre-orders for Sovereign Cause

We are now in the final week of pre-orders for the fourth Willie Morton political thriller, Sovereign Cause and it’s already clear more readers have pre-ordered this title than others in the series. Thanks to all who have pre-ordered the paperback or Kindle eBook. There is still time to pre-order, right up to publication day (1 June), when the title is distributed to selected bookshops and opens for online purchase. Copies can be purchased through this website’s Buy Andrew Scott’s Books button here https://andrewmurrayscott.scot/home/buy-my-books/ or via online retailers. At this stage it looks as if the new title will be the biggest seller yet and perhaps outsell Deadly Secrecy. Though each may be read as a standalone novel, there is strong evidence that a majority of readers return to buy previous titles or ones they have missed and the series goes from strength to strength. Thanks for your interest!

Sovereign Cause

The fourth Willie Morton political thriller is now on Pre-order until the launch on 1st June. Copies of the paperback or eBook versions can be ordered online via the “Buy Andrew’s Novels” button on the Home Page or via his Author’s page on Amazon at: https://amzn.to/2ZTuoCV where you can also catch up on previous titles in the series.

Andrew will be hosting a chat about the book on Friday 28 May on Zoom. Whether or not you have read any of the series you will be most welcome to join in the books chat and find out more about Willie Morton and it will be an opportunity to chat to the author and ask any questions you may have. To join the guest-list please send an email to: twacorbiespublishing@gmail.com or contact Andrew direct via social media or via the “Contact” button on the Home page.

All the titles can be read as standalone novels and the series is picking up readers with each new title, some of whom go back to read the previous novels. In the fourth, Willie investigates a thirty-year old conspiracy around the early death of a Treasury mandarin whose report may have been politically inconvenient and it takes him from the labyrinths of Whitehall to the back-alleys of Barcelona and into danger as two governments seek to bury a secret of the past.

Reviews and Bookshop sales

Thank goodness bookshops are back! After months of the pandemic, when there were zero bookshop sales, now bookshops are open though not entirely back to normal. My paperback sales are rising again with the sniff of future royalties in the wind. Although people were ordering online, both paperbacks and ebooks, and some authors made a big bonanza, my sales for the last four months reflect the downturn. My third title, Oblivion’s Ghost, launched online on 29 May, suffered because I had to cancel my proposed book tour and as my sales have always broadly been two or three paperbacks to each ebook sold, overall sales are down. Some good news on the bookshop front however is that a brand new bookshop has opened in my small town of Broughty Ferry! I wish The Bookhouse and all involved well and thanks for stocking my books too!

During the crisis, newspaper book reviewers have been working from home and this has caused me difficulties. Copies sent to feature editors have disappeared and in one case, repeat copies sent after phone calls never made it to a reviewer, although Oblivion’s Ghost has now been reviewed in the excellent Courier’s feature ‘Scottish Book of the Week’ and reviewed in brief in the Scots Magazine, Independence Magazine and the Scots Independent. I’m pleased to say, the review are very positive. Author interviews have also appeared in the Courier with another scheduled to appear in the Press & Journal soon. No response from Scotsman, Scotland on Sunday, Herald, Sunday Herald or the National. I had high hopes of the Irish Times but their reviewer seem to have decided not to review it after his initial willingness to look at it. I’ve been pleased to get some high ratings on Amazon and strong reviews by readers. If you’ve read and enjoyed the books, a review on Amazon or Goodreads really helps!

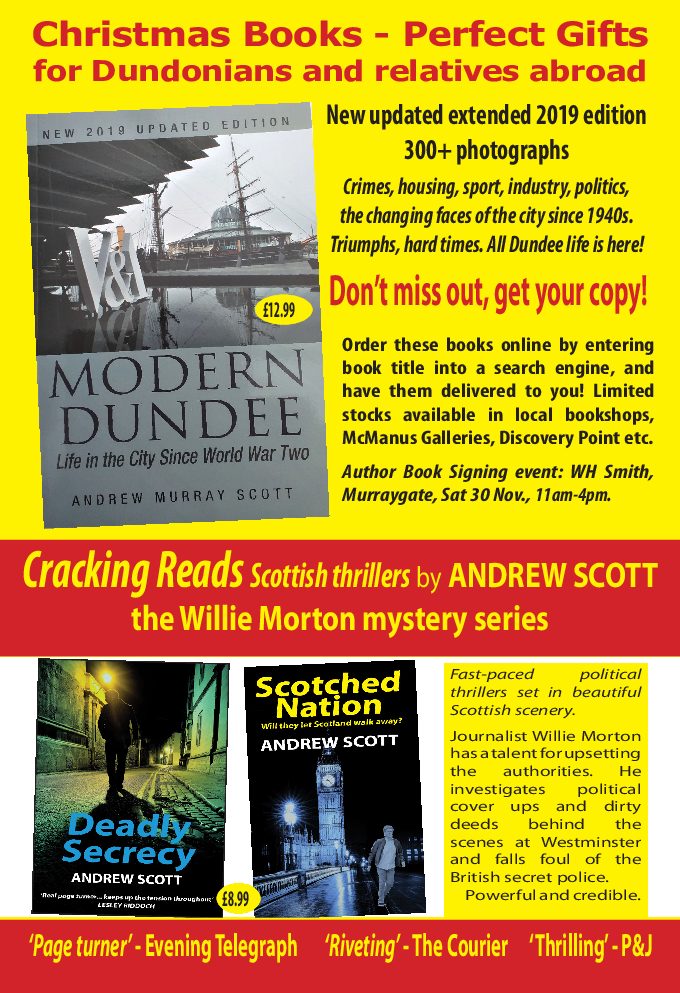

Modern Dundee by Andrew Murray Scott

Modern Dundee is Book of the Week in today’s Courier, with a 9/10 review. Here’s some comments from it: “…pays tribute to generations of Dundonians and their restless spirit… perfect Christmas gift… unique insight into the changing faces of Dundee from the 1940s, an unparalleled account of how the people of Dundee have come to define the city’s culture and heritage over the past few generations… remarkable images and written accounts… a real interactive adventure into Dundee’s recent history.” https://www.amazon.co.uk/Modern-Dundee-Andrew-Murray-Scott/dp/1780916000

BOOK OF THE WEEK 9/10 The Courier, 14.12.19

Modern Dundee: Andrew Murray Scott

Book Signing

Saturday 30 November, 11am-4pm

WH Smiths, Murraygate, Dundee.

Book Week Scotland 2019: Blether and My Books

Looking forward to this year’s Book Week Scotland programme, funded by Book Trust Scotland. I will be attending other writers’ events but also speaking at two of my own. My events this year will feature the Willie Morton thriller series that I write as Andrew Scott. I’ll be at Coldside Community Library, 150 Strathmartine Road, Dundee, on Wednesday 20th November at 2pm. Then Banff Library, High Street, Banff, on Thursday 21st November at 7pm. I’ll be reading extracts from the first two titles in the series, Deadly Secrecy and Scotched Nation. https://andrewmurrayscott.scot/home/novels/And discussing the pitfalls and pains of creating a contemporary thriller series set mainly in locations around Scotland. I hope to field some interesting questions from the audience and get a good blether going! Blether is the theme of this year’s BWS programme. It’s great that we have this annual celebration of books, reading and writing just at the start of the winter. There is nothing more pleasurable than staying in and enjoying a good book! My events are free but ticketed. Tickets and more information about the Banff event can be obtained from Live Life Aberdeenshire website / Events… Tickets for the Dundee event can be obtained from Eventbrite Andrew Scott – the Willie Morton series. The full BWS programme: https://www.scottishbooktrust.com/book-week-scotland

Video 2: Scotched Nation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cH-YSvj6eE Video 2: Scotched Nation. I created these brief videos as publicity tools to explain, as concisely as possible, the purpose and scope of my new series of political thriller fiction. The Willie Morton mystery thriller series, rooted in Edinburgh, is set around some of the most wonderful landscapes that Scotland has to offer, in many locations that are off the beaten track. An early comment on the visual quality of the writing, by (strangely enough) a Scottish publisher interested in publishing the first book, referred to the immersive nature of the writing. I decided against accepting their offer, preferring to retain, for the moment, my artistic independence, in order to establish the series. I believe the books would make excellent films as they have three of the essential ingredients: strong conflict embedded in compelling narratives about an emerging Scotland, wonderfully scenic locations for action sequences and topical themes as relevant and urgent as today’s headlines. And all of this within the structure of an ongoing fiction series involving a cast of believable characters and a quite flawed but likeable protagonist, struggling freelance journalist, Willie Morton.